a practical, cost-effective path toward making our streets more intelligent

By Julian Stromer and Steven Stromer, Jan 11, 2025

Much of today’s sidewalk and roadway infrastructure is still based on traditional materials such as concrete and asphalt. When cities attempt to incorporate intelligent systems, these technologies must be awkwardly added over, under, or around existing surfaces. A more effective approach is to integrate new technologies directly into the infrastructure itself.

Moreover, technological improvements are too often implemented in isolation, leading to inefficiencies, higher costs, maintenance challenges, and significant barriers to future upgrades.

Given the evolving demands placed on urban sidewalks and roads, alongside the opportunities created by emerging sensing and data-communication technologies, it is now possible to reimagine our streets to better meet contemporary needs. This includes preparing for the impacts of climate change and safely accommodating a wide spectrum of users — from pedestrians of all abilities to bicycles, scooters, cars, trucks, delivery fleets, and public transit vehicles.

Defining problems with city street usability

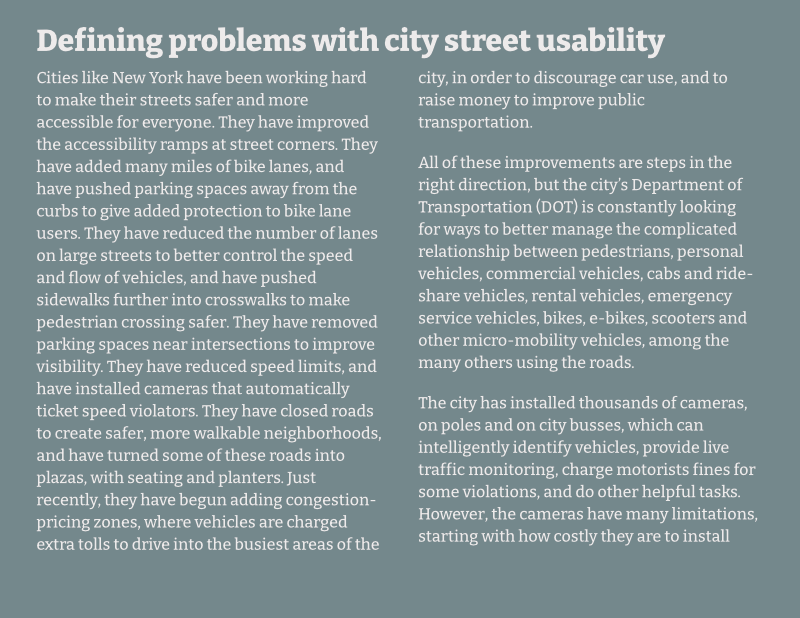

Cities such as New York have undertaken significant efforts to make their streets safer and more accessible. Accessibility ramps at corners have been modernized, and hundreds of miles of bike lanes have been added, with parking spaces shifted away from curbs to better protect cyclists. Major arterials have been redesigned with fewer lanes to moderate traffic flow, while sidewalks have been extended into crosswalks to shorten pedestrian crossings. Parking has been restricted near intersections to improve sightlines. Speed limits have been lowered and automated enforcement cameras deployed. Streets have been closed to vehicles to create walkable neighborhoods, some transformed into plazas with seating and landscaping. More recently, congestion-pricing zones have been introduced to discourage automobile use in the busiest districts and generate revenue for public transit improvements.

These initiatives represent meaningful progress, yet the Department of Transportation (DOT) continues to face the challenge of managing the complex interplay among a wide range of users: pedestrians, private automobiles, commercial trucks, taxis, ride-share services, rental vehicles, emergency responders, bicycles, e-bikes, scooters, and other forms of micro-mobility.

Thousands of cameras have been deployed on poles and buses, enabling vehicle identification, live traffic monitoring, and automated enforcement of certain violations. Yet this approach has clear limitations: high installation and maintenance costs, susceptibility to simple countermeasures such as obscured license plates, and public concerns about surveillance and intrusion.

While street design, legislation, and camera systems each contribute to safer and more efficient streets, achieving the level of performance envisioned by the DOT will ultimately require the deployment of low-cost technologies embedded across virtually every element of the built environment — sidewalks, roads, crosswalks, and curbs.

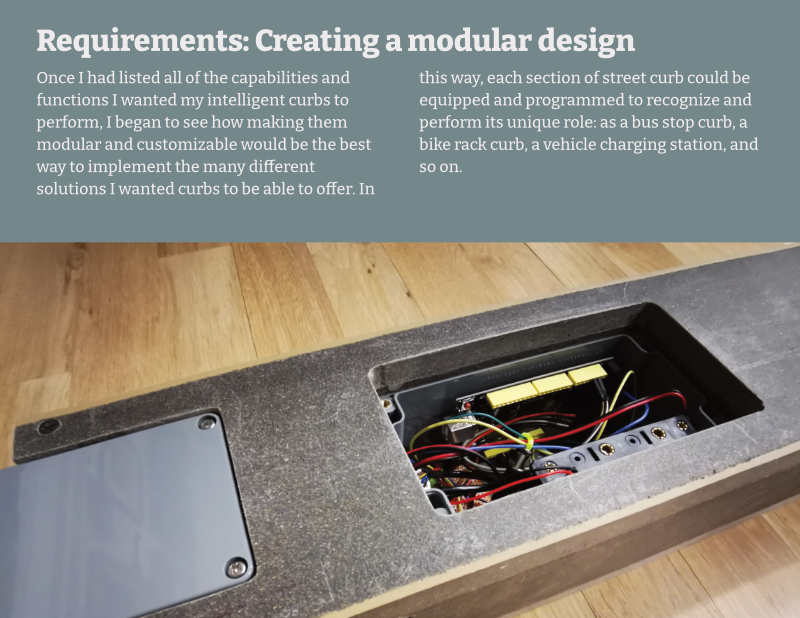

Researching possible solutions

We undertook an effort to better understand the broad spectrum of needs and opportunities associated with improving the urban street experience. Sidewalks and roadways can contribute far more to public life than their traditional function as conduits for transportation.

Direct field observations were conducted throughout New York City to document the diverse ways sidewalks and streets are utilized by different communities. These observations revealed numerous opportunities where the introduction of technology could enhance both safety and efficiency for all users.

The breadth of potential applications made two principles clear: any solution must be adaptable to evolving needs and ideas, and it must be deployable incrementally with minimal disruption to the city’s daily operations.

It became evident that intelligent sidewalks and streets would require a supporting network. Completely reconstructing pavements or roadbeds to install such infrastructure would be impractical. However, curbs emerged as a logical solution: functioning as a spine between sidewalk and roadway, they provide an accessible channel for the services required to make streets smarter. This insight was reinforced by observing city crews installing prefabricated curbs with relative ease.

Further research revealed that, although there has been limited discussion of enhancing curbs with basic smart features, no successful design, patent, or implementation of a truly technology-driven curb currently exists.

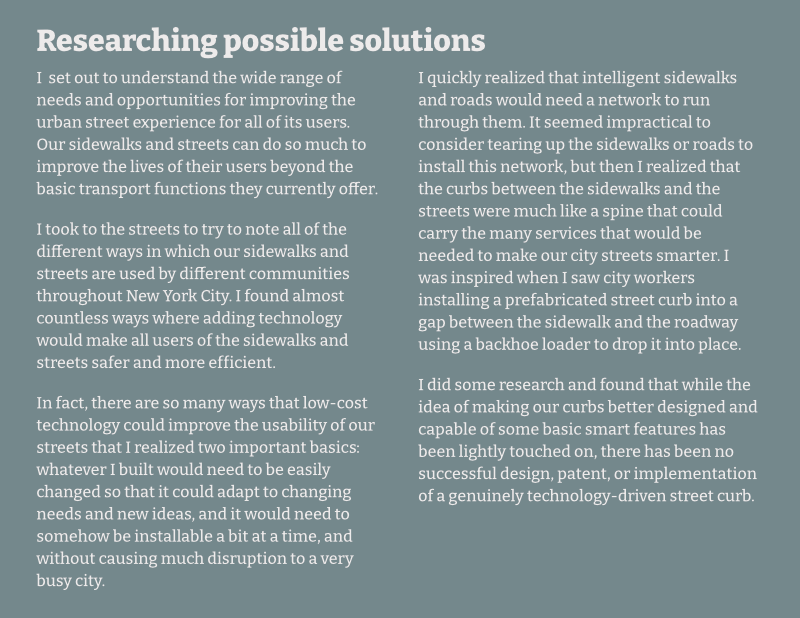

Configureable curb versions

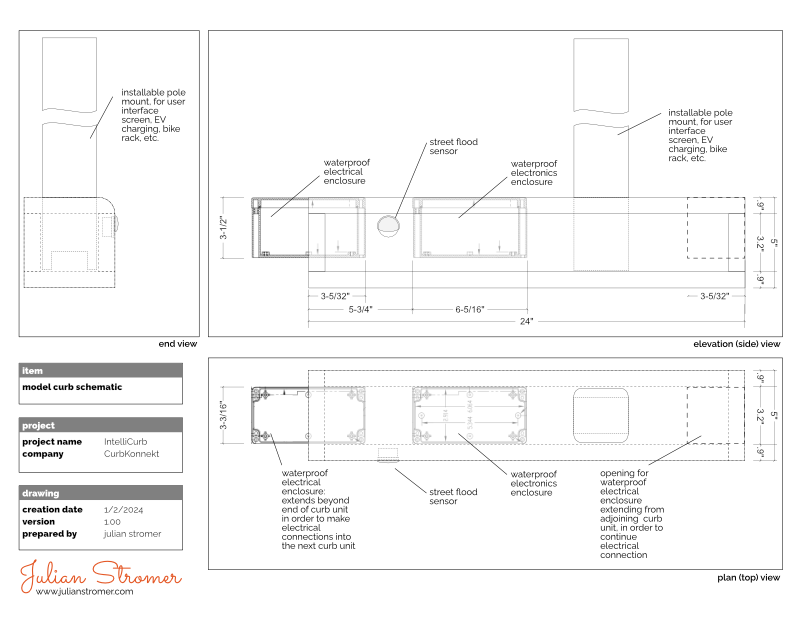

Beyond modular electronics and software, the curb system is designed with secure mounting points for devices such as parking meters, EV charging stations, bike racks, security bollards, pedestrian seating, and other peripheral infrastructure. These connection points can deliver both power and data, enabling enhanced functionality and turning each service into a potential billable feature.

standard motor vehicle parking curbs

Restores traditional parking meters, enhanced with tap-to-pay capability; meter poles can incorporate payment-enabled EV charging jacks

commercial vehicle parking curbs

Designated short-term parking for commercial vehicles, with pricing structured to remain low for brief stays but escalating rapidly to discourage extended use

drop-off and pick-up curbs

Functions like a modernized taxi stand, providing safe, designated areas where authorized ride-share drivers can pick up and drop off passengers without resorting to double parking

bus stop curbs

Equipped to identify authorized public transit vehicles, automatically extend wheelchair ramps when required, and issue citations to unauthorized vehicles

micro-mobility parking curbs

Comparable to conventional bike racks but incorporating payment-enabled charging outlets for e-vehicles such as scooters

fire hydrant curbs

Capable of automatically reporting open hydrants and issuing citations to unauthorized vehicles after a brief grace period

pedestrian seating curbs

Resembles standard public benches but includes payment-enabled electrical outlets for public convenience

bike lane separation curbs

Surface-mounted curbs that can be retrofitted onto existing streets to provide stronger separation between traffic lanes, parking areas, and bike lanes

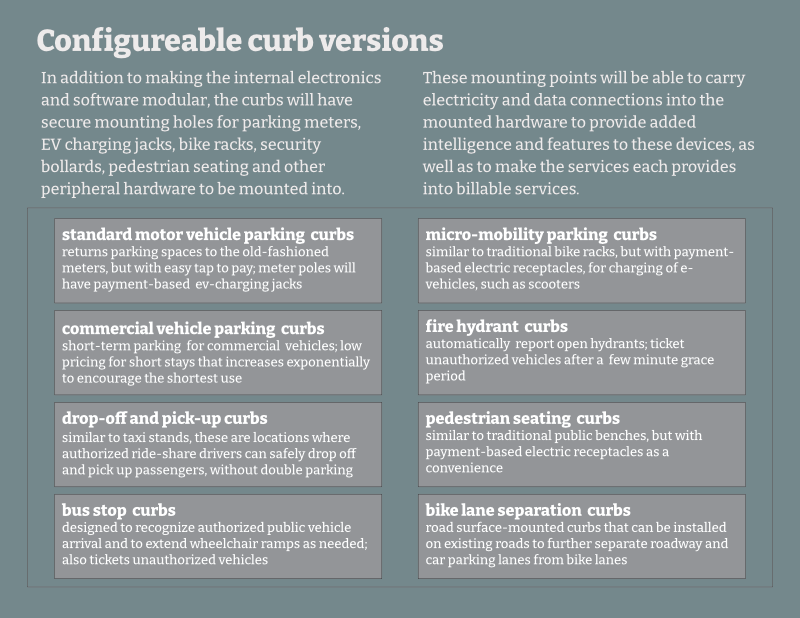

Potential capabilities and features

Drawing on research into the goals of the DOT, Emergency Services, and other city agencies, as well as prior street improvement projects and direct field observations, a set of potential capabilities and features was compiled for integration into the modular curb system. While it was not feasible to implement all of them in the initial prototype, several were incorporated to demonstrate the practicality of the underlying concept.

Public safety capabilities

- flood detection *

- fire detection

- auditory alerts for the visually impaired

- toxic gas detection (CO, H₂S, HCN, etc.)

- flammable gas detection (methane, etc.)

- chemical warfare agent detection

Traffic safety capabilities

- alerts for drivers regarding micro-mobility vehicles

- detection of vehicles encroaching onto sidewalks

Quality-of-life capabilities

- open fire hydrant detection

- idling vehicle identification (e.g., nitrogen dioxide)

Features

- modular design *

- upgradeable software

- wireless communication *

- sensor data aggregation

- cybersecurity safeguards *

- integrated payment processing

• denotes capabilities incorporated into the prototype

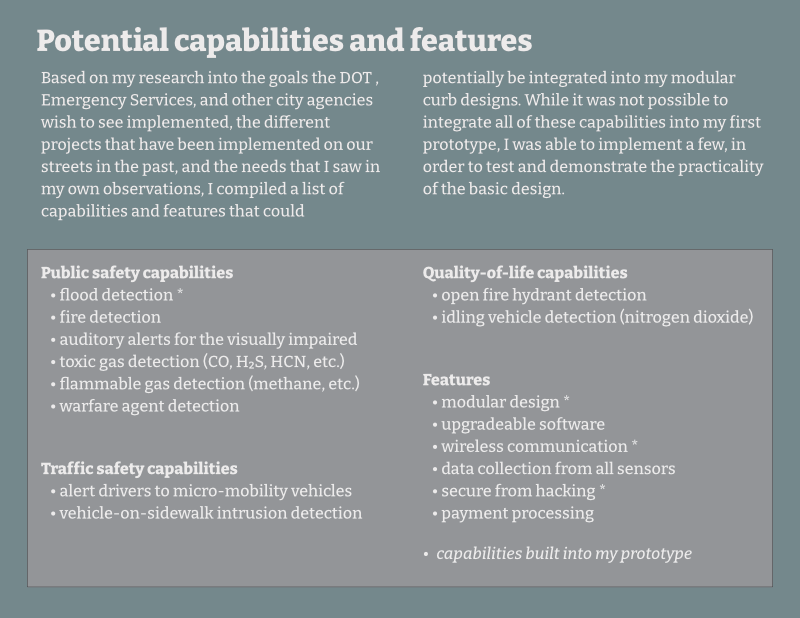

Requirements: creating a modular design

After compiling the desired capabilities and functions, it became clear that modularity and customization were essential to implementation. By designing the curbs as modular units, each section could be equipped and programmed to fulfill a distinct role — whether serving as a bus stop curb, a bike rack curb, a vehicle charging station, or another specialized application.

Requirements: selecting a suitable material

One of the earliest and most critical decisions involved identifying an alternative to the concrete and stone typically used for street curbs. Elements of street infrastructure are already being fabricated from high-strength plastics — for example, the high-visibility yellow accessibility ramps at intersections and the heavy temporary barriers deployed to redirect highway traffic during construction.

Environmental considerations: recycled plastic versus concrete

At first glance, replacing concrete with plastic may appear environmentally unsound. In practice, however, high-strength HDPE (High-Density Polyethylene) can be manufactured from recycled bottles and similar post-consumer waste. Given the substantial volume of material required for large-scale curb installation, this approach could provide a valuable use for an underutilized waste stream.

By contrast, concrete production accounts for an estimated 4–8% of global carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions, driven both by fossil-fuel combustion and by the calcination of limestone, while also representing one of the largest industrial consumers of fresh water.

Strength & Resilience

When manufactured at sufficient thickness, HDPE readily withstands the weight of cars and trucks. It is recognized for its strength, durability, and resistance to both chemicals and impact. The material is also highly resistant to ultraviolet radiation, effectively waterproof, heat tolerant, low-maintenance, and impervious to infestation, fungal growth, and rot. While not entirely immune to wear, HDPE compares favorably to concrete, which often degrades more quickly due to freeze-thaw cycles.

Requirements: making street curbs ‘communicate’

At first glance, connecting curbs with physical wiring might seem logical, but this presents several challenges: extending wires across roadways is impractical, and a single break could disable entire sections while remaining difficult to locate and repair. A more effective approach is wireless communication, whereby curbs within several blocks report to a central hub, which then relays information to a main control station.

Conventional Wi-Fi, familiar from household use, struggles to maintain connectivity even across short indoor distances, making it unsuitable for communication over one to two miles. Cellular networks can provide broader coverage, but they are owned by private carriers that impose usage fees, and they typically fail during power outages when towers lose electricity.

An alternative exists in the form of LoRa (Long Range), a low-cost wireless technology capable of operating across several miles without reliance on private carriers. LoRa operates in unlicensed frequency bands and requires no federal regulation or licensing, making it an attractive option for municipal infrastructure.

What is LoRa?

LoRa is a radio technology developed for low-power, low–bit rate Internet of Things (IoT) applications. Operating in sub-gigahertz frequency bands (902–928 MHz in North America), it requires no licensing. Data rates range from 0.3 to 27 kbit/s — insufficient for bandwidth-heavy content like images or video, but ideal for transmitting sensor data. Remarkably, devices scarcely larger than a coin can transmit signals across distances of up to twelve miles.

Requirements: securing curbs from hacking

Securing networked infrastructure requires attention across multiple layers.

The physical layer

The first priority is protecting against physical intrusion. At this level, curbs must be safeguarded against tampering. For example, sensors can be installed to detect when a cover is opened; upon detection, the unit immediately alerts the central station and takes itself offline until the access is reviewed and authorized.

The hardware layer

The hardware layer encompasses the CPU, networking devices, and other electronics within the curb. The system software can record all hardware changes — such as a sensor disconnection — and immediately report them to the central station, triggering alerts to the appropriate authorities if changes occur without authorization.

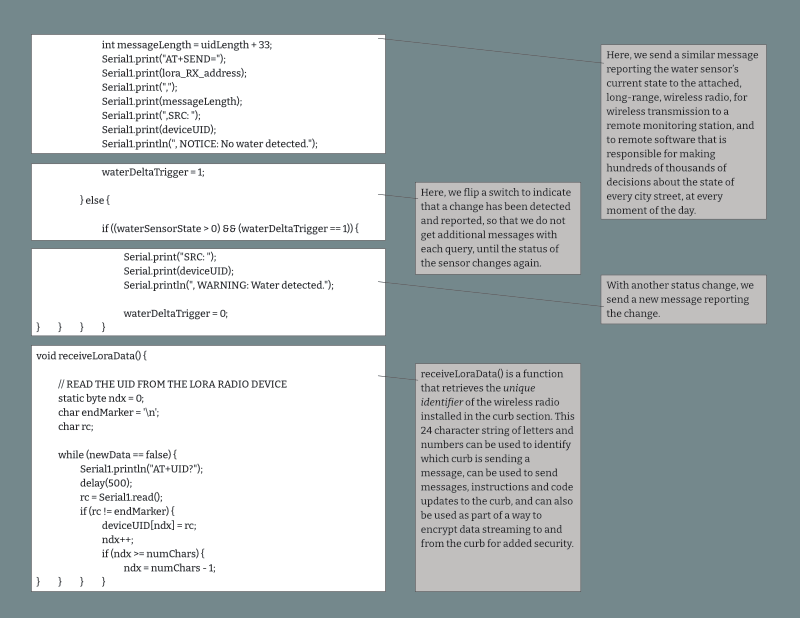

Each curb’s LoRa radio carries a unique identifier that is difficult to replicate. This ensures that attempts by unauthorized devices to join the network, or to impersonate authorized units, can be detected and blocked.

The network layer

LoRa radios also support point-to-point encryption, ensuring that any intercepted transmissions remain unreadable.

Only as secure as needed

Finally, it is important to recognize that data from individual curbs is not highly sensitive. In many cases, the greatest public value would come from openly sharing this information with residents and visitors.

Sources

LoRa Radio

YouTube: Data Slayer, You’ve Never Seen WiFi Like This

Esclabs.in: Edison Science Corner, How to interface LoRa module with Arduino | Reyax RYLR998

YouTube: Mario's Ideas, Arduino meets RYLR998: A Comprehensive Guide to LoRa Module Integration

thethingsnetwork.org: Duty Cycle

SunfireTesting.com: Tim Payne, LoRa FCC Certification Guide

Water Sensor

Electronicsforu.com: Fully Non-invasive Liquid Level Detection

Force Sensitive Resistor

Sparkfun.com: jimblom and bboyho, Force Sensitive Resistor Hookup Guide

Ambient Light Sensor

AllDatasheet.com: Everlight Ambient Light Sensor Datasheet

DFRobot.com: Gravity Analog Ambient Light Sensor

DFRobot.com: Analog Ambient Light Sensor

NYC Department of Transportation Planning

NYC.gov: NYC SmartCurbs Project, NYC DOT Curb Management Action Plan.pdf